Prepared remarks: Attorney General Phil Weiser at George Mason Law Review 24th Annual Antitrust Symposium (Feb. 16, 2021)

Meeting this Antitrust Moment

More than any time in recent history—some would say in over a century—antitrust now looms large in the public imagination and discussion. Within the last several years, both scholars and popular commentators have focused on the decrease in competition and the increased level of concentration in the U.S. economy, explaining its adverse impact on consumers, workers, and innovation—and even income inequality. The concerns that the U.S. economy is hurting on account of a lack of competition—and rising concentration—were powerfully captured in a 2016 Obama Administration Council of Economic Advisors report, “The Benefits of Competition and Indicators of Market Power.” Since that report, the concerns about the decline of competition have gained bipartisan traction, raising the question of how we meet the challenges of this antitrust moment.

In this essay, I outline some initial observations and suggestions for revitalizing antitrust at this important time in our nation’s history. Part I discusses the decline of competition and increased level of concentration in our economy and how these circumstances differ from the 1960s and 1970s when the Chicago School of antitrust criticized antitrust enforcement as untethered from economics. Part II evaluates two consequences of more concentrated markets—enhanced opportunities for coordination or collusion by incumbent firms and the impact of vertical mergers (between a supplier and distributor, for example) on competition. Part III examines the role of monopolization law and the antitrust cases filed against Facebook and Google. Part IV offers a short conclusion.

I. A Revolution in Thinking

In the 1960s, some commentators and antitrust enforcers rarified the role of small businesses as an end in and of itself, arguing that mergers of any notable size should be barred. In that era, mergers were generally not analyzed based on their likely competitive effects. Consider, for example, United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., where the Supreme Court enjoined a merger of two grocery chains with a combined market share of just 7.5%. That decision famously represented a “big is bad” attitude and fueled the Chicago School of antitrust law that focused on actual economic consequences and critiqued such decisions.

Justice Stewart’s Von’s Grocery dissent anticipated the Chicago School critique, calling out the majority opinion for its lack of rigor. For starters, Justice Stewart commented that the opinion made “no effort to appraise the competitive effects of this acquisition in terms of the contemporary economy of the retail food industry in the Los Angeles area.” Notably, Justice Stewart skewered the majority for adopting a per se rule against mergers in the face of any trend towards concentration, ignoring that small businesses were competing effectively against the larger chains and overlooking that there were not significant barriers to entry. Finally, Justice Stewart took a few shots at the majority’s overall approach, noting that “the emotional impact of a merger between the third and sixth largest competitors in a given market, however fragmented, is understandable, but that impact cannot substitute for the analysis of the effect of the merger on competition” and “the sole consistency that I can find is that in litigation under [the antitrust laws], the Government always wins.”

The Chicago School critique, which was led in the 1970s and 1980s by leading scholars (and later judges) like Robert Bork, Richard Posner, and Frank Easterbrook, highlighted the importance of economic rigor and a focus on market realities. This critique paved the groundwork for the development of the joint merger guidelines adopted by both the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission in 1992 and revised in 1997 and 2010, which set forth an economic foundation for merger review. Notably, instead of suggesting that all increases in concentration would violate the antitrust laws, the guidelines adopted the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and a focus on the market shares of the top four firms in a defined product market. Under the 2010 Guidelines, for example, a market is highly concentrated and mergers presumptively illegal after the market reaches a level of 2500 HHI, reflecting a market of four equally sized rivals.

For a contrast to Von’s Grocery, consider the Ninth Circuit’s 1990 decision in United States v. Syufy Enterprises. That case involved movie theatres in Las Vegas. In particular, the Justice Department challenged Syufy’s acquisition of competing theatres as a violation of the antitrust laws. Unlike Von’s Grocery, the Syufy court ruled against the Justice Department, invoking the Department’s own merger guidelines and pointing to the absence of barriers to entry. And the Ninth Circuit drove this point home by highlighting the empirical realities of the market: “Syufy’s acquisitions did not short circuit the operation of the natural market forces; Las Vegas’ first-run film market was more competitive when this case came to trial than before Syufy bought out Mann, Plitt and Cragin.” In short, within a generation, the Justice Department went from receiving every benefit of the doubt in challenging a merger to being put to the test to prove competitive harm based on economic rigor.

The Chicago School critique, or revolution as some have called it, recast antitrust law within a generation. The change was not only from Von’s Grocery to Syufy in the analysis of mergers between competitors (horizontal mergers), but also in the analysis of “vertical” relationships (terms of dealing between suppliers and distributors). Most notably, within a little more than a decade, the Supreme Court changed its tune on the proper mode of analyzing requirements imposed by suppliers on distributions. In Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., the Supreme Court overruled United States v. Arnold, Schwinn & Co., holding that a supplier’s imposition of terms on a distributor—in this case, retailers’ franchise territories—were no longer per se illegal, but should be analyzed under the rule of reason to determine their actual economic impact.

In the context of the facts of GTE Sylvania, the ruling was a victory for economics, the Chicago School, and common sense. After all, Sylvania’s TV manufacturing business was a small part of the overall market, with around a 1% market share. In GTE Sylvania, the Court’s emphasis on inter-brand competition—Sylvania’s competition with rival TV manufacturers—over intrabrand competition—rivalry between distributors who sold Sylvania TV sets—made a ton of sense. But as Justice White noted in his concurrence in the judgment, there is a potential difference in the relative competitive significance between interbrand competition versus intrabrand competition in a highly concentrated market.

In today’s economy, skepticism towards antitrust enforcement is far less warranted than it was during Von’s Grocery (1966), GTE Sylvania (1977), or even Syufy (1990). After all, as Carl Shapiro recently explained, “evidence that U.S. markets have become more concentrated, evidence that price/cost margins have risen, evidence that entry barriers have become higher, and evidence that corporate profits have risen substantially and are expected to persist” all support the need for more active merger enforcement. Indeed, we are now a world away in terms of the level of competition from that earlier era, meaning that more vigilance is called for both in overseeing mergers and vertical integration. The next Part will discuss those challenges.

II. The Critical Role of Merger Enforcement

The role of governmental antitrust enforcement is not merely to police anticompetitive conduct, but also to set rules of the road for an administrable antitrust system. Such rules enable firms to self-police based on their understanding of the relevant boundaries, with antitrust lawyers able to counsel them on how to do so. In principle, the Merger Guidelines provide valuable guidance in this respect. But in practice, firms push the envelope to test what actions enforcers will challenge as illegal.

Today’s cause for concern is not overly aggressive antitrust enforcement, but that increasing industry concentration is harming consumers, workers, and innovation. For a case in point, consider the airline industry. As a group of commentators related, “between 2005 and 2014, the Antitrust Division reviewed seven airline mergers, in five of those cases, there were no challenges, and the Antitrust Division settled the other two. Now, four airlines control almost 70 percent of domestic air travel in the United States.” And because consumers are basically limited to the flights available from nearby local airports, this means that, in practice, most consumers are left to choose between two or three airlines when making travel plans. There is also little to no entry in this sector, as discussed in the next part, in part because incumbent airlines have developed a reputation for predation. Finally, in what demonstrates the clear consumer harm from the high level of concentration in the airline industry, consider that when fuel prices fell dramatically, consumers did not see any benefits passed on to them, but rather the industry recorded massive profits.

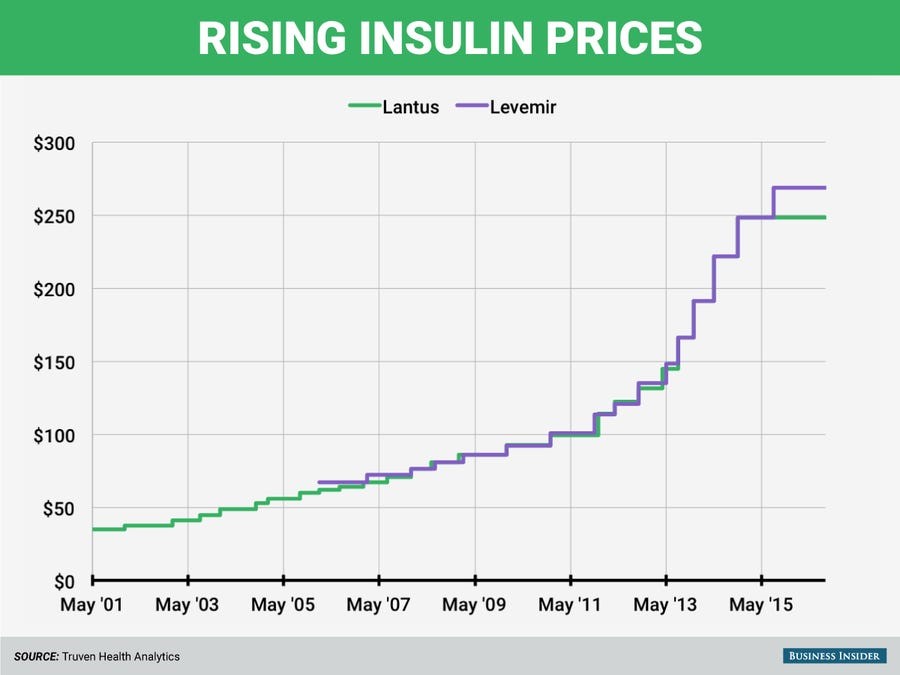

What is taking place in the airline industry is far from unique. Consider, for another example, the case of the pharmaceutical industry and the market for insulin. Our office recently studied this market, asking why insulin prices rose so much faster than the rate of inflation and issuing a report calling for action to promote competition. The answer we found: with only three firms in the marketplace, their pricing patterns were troubling at best. Figure 1 below captures the situation between two incumbent firms.

What these numbers do not capture is the impact on people, especially the most vulnerable among us, such as those without health care insurance, who end up paying even more for insulin, a life-saving drug. In our survey of Colorado consumers, we heard from many individuals who suffered on account of these rising prices, including the over “40 percent of survey respondents who are forced to ration their use of this life-saving product at least once a year and who, in some cases, “even choose to fast as a means of managing their blood sugar levels.”

In industries with few competitors, such as the three firms that provide insulin, a practice of lock-step pricing or tacit collusion is both appealing and feasible. On the front end, the best strategy to prevent such a dynamic is effective merger control, preventing markets like airlines or pharmaceuticals from becoming overly concentrated. On the back end, competition policy should encourage and enable entry, such as some of the patent reform steps we advocate in the insulin report. And where enforcers can identify quid-pro-quo collusion—such as price fixing—it is critical that they take action, as a coalition of State Attorneys General are doing in a case against generic drug companies who have raised prices through cartel-like behavior.

Finally, it bears emphasis that the increasing industry concentration can also lead to a more difficult environment for entry and innovation where dominant firms control critical inputs necessary for entry. This dynamic can be created or exacerbated by vertical mergers. As a result of such mergers, dominant firms can harm competition by gaining control over and then restricting access to a critical input—say, by raising its price or degrading its quality. In some cases, such action can involve foreclosing a distribution channel (for example, limiting access to sales channel); in others, it can involve acquiring a critical component part of a product (for example, a cable company buying video programming).

In the spring of 2019, our office confronted such a concern and took action to protect competition in the Medicare Advantage market by preventing a vertical merger between UnitedHealth and DaVita that would have impaired competition by eliminating a competitor’s access to a critical input. In the years leading up to the merger, the health insurance provider Humana had entered the Medicare Advantage market in Colorado Springs and eroded the market share of UnitedHealth, the dominant firm, from around 75% to around 50%. Critical to Humana’s success in this market was its relationship with DaVita’s clinics, which referred patients to Humana’s Medicare Advantage offering and might well cease to do so in the wake of UnitedHealth’s proposed merger with DaVita. While the FTC declined to take action to address this competitive harm in Colorado, our office did so, imposing a remedy that protected competition in this market, with the aid of the FTC staff and the support of two FTC Commissioners.

For another powerful case in point, and reflection of the state of our economy, consider the case of Steves and Sons, Inc. v. Jeld-Wen, Inc, involving the door manufacturing business. In 2000, this industry was robustly competitive with a large number of door manufacturers able to operate independently and buy critical component parts, including interior molded doorskins. At that time, there were two manufacturers of this component part, Masonite and JELD-WEN; JELD-WEN, however, was vertically integrated, meaning that it both manufactured doorskins as well as used them internally to sell finished doors. In 2001, Masonite – including its premier manufacturing plant in Towanda, Pennsylvania – was set to be sold to Premdor, one of the then-independent door manufacturing firms. In response to concerns by independent door manufacturers, the Justice Department required the divestiture of the Towanda plant from Premdor and the establishment of a new firm, Craftmaster International, Inc (CMI), which would be able and motivated to sell doorskins to independent door manufacturers. And from 2002-2012, CMI did just that, continuing the status quo ante before the Masonite-Premdor merger and providing a third rival seller of molded doorskins.

In 2012, JELD-WEN expressed an interest in acquiring CMI, but before consummating the deal and approaching the Justice Department, it “entered into long-term supply contracts with the Independents, knowing that this oft-used tactic would assuage the concerns of the Justice Department and the Independents about anticompetitive effects of the merger.” JELD-WEN’s tactic was successful, as when the Justice Department contacted independent firms like Steves, they expressed no concerns about the merger, citing the long-term supply agreement. And, once the merger was consummated, JELD-WEN closed one of its existing plants and, notwithstanding declining costs, it proceeded to raise prices to Steves and other independent firms under the supply agreement. JELD-WEN also changed its policy on reimbursing Steves for the cost of doors rendered defective by flawed doorskins. In making these changes, JELD-WEN took advantage of its role as the only supplier of doorskins to independent door manufacturers, even sending Steves a public presentation that Masonite had made to investors stating that it would not sell doorskins to the independents firms.

In 2016, Steves took the unprecedented step of challenging the 2012 merger as illegal and calling for divestiture of CMI from JELD-WEN. Steves demonstrated the adverse competitive consequences outlined above as well as provided evidence that it was unable to meet its need for doorskins from either foreign sources or establishing its own source of domestic supply. Acknowledging that divestiture is the “most drastic, but most effective, of antitrust remedies[,]” the court ultimately turned to history as its guide in justifying this step:

in the spring of 2012, there were three vertically integrated doorskin suppliers: Masonite, JELD-WEN; and CMI. The record shows that these three companies competed vigorously in selling doorskins to Steves and the other independent (non-integrated) door manufacturers. That is pointedly illustrated by the fact that, in 2011 and 2012, Steves was in negotiations for a new long-term supply contract, and there was significant price competition for Steves’ business.

The arc of merger law—from Von’s Grocery to Steves—captures both the value of the Chicago School critique and its overreach. To defend the merger in Steves and to oppose antitrust enforcement in cases like it is an unjustified extension of the original Chicago School critique. Stated more broadly, the central challenge for antitrust law today is not to tame overenforcement akin to Von’s Grocery, but to address the risk of underenforcement made plain by a case like Steves. After all, if this private action unearthed what was clearly an anticompetitive merger, how many other such mergers have gone through and not been examined after the fact? The facts of the Steves case, along with the lack of competition in the airline and pharmaceutical industries, underscore that consumers, workers, and innovative firms are hurt when the lack of antitrust enforcement allows for firms to establish and maintain market power.

III. Dominant Firms and the Role of Section 2

Over the last several decades, the Supreme Court has undermined the path for curbing the harm to competition from monopolies under Section 2 of the Sherman Act by erecting a series of artificial hurdles for enforcers to meet. For one such example, consider the impact of Brooke Group v. Brown & Williamson Corp., which addressed the law of predatory pricing. In Brooke Group, the Court imposed both a price-cost test (predatory pricing involves pricing below costs) and a recoupment test (meaning that a plaintiff must demonstrate a likelihood of profiting from the practice). In so doing, the Court—quite purposefully—suggested that predatory pricing is rare and may even be implausible. In response, we have seen a very limited use of this doctrine over the last quarter century.

As explained earlier, the once vibrant wave of entry into the airline industry has subsided and a wave of concentration has led to market power that has hurt consumers. One of the reasons behind the lack of entry is the failure of antitrust to address predation by dominant firms. Notably, in the face of a successful effort by American Airlines to exclude a rival through predatory pricing, the Tenth Circuit rejected the USDOJ’s lawsuit. In particular, it held that even though American Airlines ramped up capacity and reduced prices dramatically in response to the entry of a low cost carrier, it concluded that it had not engaged in unlawful below cost pricing because of how it viewed the opportunity cost of rerouting an airplane. With that unfortunate conclusion in hand, the court did not fully wrestle with, as Scott Hemphill & I put it, whether the recoupment test could be satisfied when a firm developed “a reputation for predation by its conduct in one or multiple markets, and thereby deter[ed] entry into and preserve[d] monopoly profits in other markets.”

The ability of an incumbent monopolist to deter entry and competition through developing a reputation for predation has created increasing concern among economists. In the recently filed case against Facebook, a coalition of states developed this very argument as a basis of Section 2 liability. In short, we argued that Facebook engaged in a campaign of threatening to “buy or bury” its rivals. As a result, rivals were given a choice—to be purchased in their infancy or face “the wrath of Mark [Zuckerberg],” meaning a denial of access to critical opportunities (such as the ability to use Facebook to sign in to a service) that could undermine its business. Facebook’s goal, in other words, was to buy upstart rivals before they emerged as serious threats or to degrade their ability to compete on the merits.

Like the Steves case, the case against Facebook involves a careful review of what happened in the wake of a consummated merger. In particular, it evaluated the impact of the “buy or bury” strategy and recognized that Facebook abused its monopoly power by purchasing upstart rivals—Instagram and WhatsApp in particular—to protect its dominant position in the personal social networking market. Consequently, the complaint alleged violations of Section 7 of the Clayton Act and Section 2 of the Sherman Act, asking for both divestiture relief as well as oversight of Facebook’s platform so it could not engage in discriminatory access for purposes of excluding rivals’ ability to compete on the merits.

The case against Google echoes the case against Microsoft from a generation earlier. In Microsoft, a unanimous D.C. Circuit concluded that Microsoft took a series of actions, including entering into exclusionary contracts, degrading access to its platform, and keeping barriers to entry artificially high, that excluded technologies that threatened to erode its operating system monopoly. This victory reflected the significance and importance of presenting a thorough factual analysis, proven at trial, that demonstrated how an incumbent monopolist engaged in exclusionary conduct not justified on efficiency grounds. In the case of Google, it has taken a series of actions that have sought to defend and entrench its monopolies in search and search advertising, including entering into exclusionary contracts and inhibiting the ability of other companies to acquire customers of their own. In both cases, the companies faced threats to their dominance from an adjacent sector and responded, not by competing on the merits, but by undermining the ability of rivals to compete. To remedy such conduct and restore competition requires not merely ending the illegal conduct, but taking affirmative steps to “lower the barriers to entry.”

IV. Conclusion

We are living at a moment that calls for bold antitrust leadership. The trend in antitrust doctrine, however, is to impose unwarranted obstacles to enforcement, which is leading Congress to consider whether legislative action is necessary to remove these obstacles. One important role for antitrust enforcement is to recognize the power of bringing and proving cases that demonstrate clear instances of harm to competition. In that sense, the cure for the unwarranted extension of Chicago School thinking is a focus on what got the Chicago School critique started: paying attention to marketplace realities, not rigid formalities.

To appreciate the value of a focus on marketplace realities, consider the Evanston Northwestern hospital case. Before that case, the FTC had lost seven hospital merger cases in a row. As related by former FTC Chairman Muris, some suggested that, in the face of that track record, the FTC should “give up on hospital mergers.” It declined to do so. Instead, the FTC did a series of retrospective studies, identified an already consummated merger, and demonstrated the harm to competition from a hospital merger in the Evanston Northwestern case. With the empirical realities of a hospital merger demonstrated with a clear showing of price increases, courts have re-evaluated the prior use of rigid formal tests (the misuse of the Elzinga-Hogarty patient-flow test) and have condemned other hospital mergers as anticompetitive.

Following the lessons of Evanston Northwestern, the Microsoft case, and the Steves case, the challenge for antitrust will be to demonstrate concrete factual situations that call for a re-assessment of legal standards now tilted to guard against the risk of over-enforcement while undervaluing the real harm caused by under-enforcement. That tilt, however, is no longer justified by current market realities.

As a new Administration considers how to elevate and revitalize competition policy goals, it will have the opportunity to both reinvigorate antitrust enforcement and promote competition more broadly. As some commentators have explained, there is an opportunity for a broader assessment of how to promote competition—beyond antitrust enforcement—by establishing a new “White House Office of Competition Policy” and engaging in robust and careful studies of industries to better understand how and why competition issues arise, such as in agriculture or health care. And at this important moment, it will also be crucial for antitrust commentators to frame a post-Chicago School agenda for antitrust law attuned to today’s market realities.